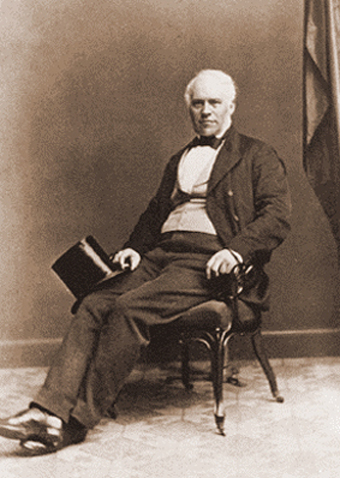

A Life's Work

Exhibition to mark the bicentenary of the birth of Jón Sigurðsson held by the National and University Library of Iceland in collaboration with the Jón Sigurðsson Birthday Committee, and with contributions from the National Archives, National Museum, Árni Magnússon Institute for Icelandic Studies and the Alþingi Archive.